Hydropower

Hydropower, hydraulic power or water power is power that is derived from the force or energy of moving water, which may be harnessed for useful purposes.

Prior to the widespread availability of commercial electric power, hydropower was used for irrigation, and operation of various machines, such as watermills, textile machines, sawmills, dock cranes, and domestic lifts.

Another method used a trompe to produce compressed air from falling water, which could then be used to power other machinery at a distance from the water.

Contents |

History

Early uses of waterpower date back to Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, where irrigation has been used since the 6th millennium BC and water clocks had been used since the early 2nd millennium BC. Other early examples of water power include the Qanat system in ancient Persia and the Turpan water system in ancient China.

Waterwheels and mills

Hydropower has been used for hundreds of years. In India, water wheels and watermills were built; in Imperial Rome, water powered mills produced flour from grain, and were also used for sawing timber and stone; in China, watermills were widely used since the Han Dynasty. The power of a wave of water released from a tank was used for extraction of metal ores in a method known as hushing. The method was first used at the Dolaucothi gold mine in Wales from 75 AD onwards, but had been developed in Spain at such mines as Las Medulas. Hushing was also widely used in Britain in the Medieval and later periods to extract lead and tin ores. It later evolved into hydraulic mining when used during the California gold rush.

In China and the rest of the Far East, hydraulically operated "vigina wheel" pumps raised water into irrigation canals. At the beginning of the Industrial revolution in Britain, water was the main source of power for new inventions such as Richard Arkwright's water frame.[1] Although the use of water power gave way to steam power in many of the larger mills and factories, it was still used during the 18th and 19th centuries for many smaller operations, such as driving the bellows in small blast furnaces (e.g. the Dyfi Furnace)[2] and gristmills, such as those built at Saint Anthony Falls, utilizing the 50-foot (15 m) drop in the Mississippi River.

In the 1830s, at the peak of the canal-building era, hydropower was used to transport barge traffic up and down steep hills using inclined plane railroads.

Hydraulic power pipes

Hydraulic power networks also existed, using pipes carrying pressurized liquid to transmit mechanical power from a power source, such as a pump, to end users. These were extensive in Victorian cities in the United Kingdom. A hydraulic power network was also in use in Geneva, Switzerland. The world famous Jet d'Eau was originally only the over pressure valve of this network.[3]

Natural manifestations

In hydrology, hydropower is manifested in the force of the water on the riverbed and banks of a river. It is particularly powerful when the river is in flood. The force of the water results in the removal of sediment and other materials from the riverbed and banks of the river, causing erosion and other alterations.

Modern usage

There are several forms of water power currently in use or development. Some are purely mechanical but many primarily generate electricity. Broad categories include:

- Damless hydro, which captures the kinetic energy in rivers, streams and oceans.

- Hydroelectricity, usually referring to hydroelectric dams, or run-of-the-river setups (e.g. hydroelectric-powered watermills).

- Marine current power which captures the kinetic energy from marine currents.

- Ocean thermal energy conversion which exploits the temperature difference between deep and shallow waters.

- Osmotic power, which channels river water into a container separated from sea water by a semipermeable membrane.

- Tidal power, which captures energy from the tides in horizontal direction.

- Tidal stream power, which does the same vertically.* Vortex power, which creates vortices which can then be tapped for energy.

- Waterwheels, used for hundreds of years to power mills and machinery.

- Wave power, which uses the energy in waves.

Hydroelectric dams

Hydroelectric power now supplies about 715,000 megawatts or 19% of world electricity.[4] Large dams are still being designed. The world's largest is the Three Gorges Dam on the third longest river in the world, the Yangtze River. Apart from a few countries with an abundance of hydro power, this energy source is normally applied to peak load demand, because it is readily stopped and started. It also provides a high-capacity, low-cost means of energy storage, known as "pumped storage".

Hydropower produces essentially no carbon dioxide or other harmful emissions, in contrast to burning fossil fuels, and is not a significant contributor to global warming through CO2.

Hydroelectric power can be far less expensive than electricity generated from fossil fuels or nuclear energy. Areas with abundant hydroelectric power attract industry. Environmental concerns about the effects of reservoirs may prohibit development of economic hydropower sources.

The chief advantage of hydroelectric dams is their ability to handle seasonal (as well as daily) high peak loads. When the electricity demands drop, the dam simply stores more water (which provides more flow when it releases). Some electricity generators use water dams to store excess energy (often during the night), by using the electricity to pump water up into a basin. Electricity can be generated when demand increases. In practice the utilization of stored water in river dams is sometimes complicated by demands for irrigation which may occur out of phase with peak electrical demands.

Not all hydroelectric power requires a dam; a run-of-river project only uses part of the stream flow and is a characteristic of small hydropower projects. A developing technology example is the Gorlov helical turbine.

Tidal power

Harnessing the tides in a bay or estuary has been achieved in France (since 1966), Canada and Russia, and could be achieved in other areas with a large tidal range. The trapped water turns turbines as it is released through the tidal barrage in either direction. A possible fault is that the system would generate electricity most efficiently in bursts every six hours (once every tide). This limits the applications of tidal energy; tidal power is highly predictable but not able to follow changing electrical demand.

Tidal stream power

A relatively new technology, tidal stream generators draw energy from currents in much the same way that wind generators do. The higher density of water means that a single generator can provide significant power. This technology is at the early stages of development and will require more research before it becomes a significant contributor. Several prototypes have shown promise.

Wave power

Harnessing power from ocean surface wave motion might yield much more energy than tides. The feasibility of this has been investigated, particularly in Scotland in the UK. Generators either coupled to floating devices or turned by air displaced by waves in a hollow concrete structure would produce electricity. For countries with large coastlines and rough sea conditions, the energy of waves offers the possibility of generating electricity in utility volumes.

Small scale hydropower

Small scale hydro or micro-hydro power has been increasingly used as renewable energy source, especially in remote areas where other power sources are not viable. Small scale hydro power systems can be installed in small rivers or streams with little or no discernible environmental effect on things such as fish migration. Most small scale hydro power systems make no use of a dam or major water diversion, but rather use water wheels. Many areas of the North Eastern United States have locations along streams where water wheel driven mills once stood. Sites such as these can be renovated and used to generate electricity. Also, small scale hydro power plants can be combined with other energy sources as a supplement. For example a small scale hydro plant could be used along with a system of solar panels attached to a battery bank. While the solar panels may create more power during the day, when the majority of power is used, the hydro plant will create a smaller, constant flow of power, not dependent on the sunlight.

There are some considerations in a micro-hydro system installation. The amount of water flow available on a consistent basis, since lack of rain can affect plant operation. Head, or the amount of drop between the intake and the exit. The more head, the more power that can be generated. There can be legal and regulatory issues, since most countries, cities, and states have regulations about water rights and easements.

Over the last few years, the US Government has increased support for alternative power generation. Many resources such as grants, loans, and tax benefits are available for small scale hydro systems.

In poor areas, many remote communities have no electricity. Micro hydro power, with a capacity of 100 kW or less, allows communities to generate electricity.[4] This form of power is supported by various organizations such as the UK's Practical Action.[5]

Micro-hydro power can be used directly as "shaft power" for many industrial applications. Alternatively, the preferred option for domestic energy supply is to generate electricity with a generator or a reversed electric motor which, while less efficient, is likely to be available locally and cheaply.

Resources in the United States

There is a common misconception that economically developed nations have harnessed all of their available hydropower resources. In the United States, according to the US Department of Energy, "previous assessments have focused on potential projects having a capacity of 1 MW and above". This may partly explain the discrepancy. More recently, in 2004, an extensive survey was conducted by the US-DOE which counted sources under 1 MW (mean annual average), and found that only 40% of the total hydropower potential had been developed. A total of 170 GW (mean annual average) remains available for development. Of this, 34% is within the operating envelope of conventional turbines, 50% is within the operating envelope of microhydro technologies (defined as less than 100 kW), and 16% is within the operating envelope of unconventional systems.[6] In 2005, the US generated 1012 kilowatt hours of electricity. The total undeveloped hydropower resource is equivalent to about one-third of total US electricity generation in 2005. Developed hydropower accounted for 6.4% of total US electricity generated in 2005.

Calculating the amount of available power

A hydropower resource can be measured according to the amount of available power, or energy per unit time. In large reservoirs, the available power is generally only a function of the hydraulic head and rate of fluid flow. In a reservoir, the head is the height of water in the reservoir relative to its height after discharge. Each unit of water can do an amount of work equal to its weight times the head.

The amount of energy, E, released when an object of mass m drops a height h in a gravitational field of strength g[7] is given by

The energy available to hydroelectric dams is the energy that can be liberated by lowering water in a controlled way. In these situations, the power is related to the mass flow rate.

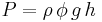

Substituting P for E⁄t and expressing m⁄t in terms of the volume of liquid moved per unit time (the rate of fluid flow, φ) and the density of water, we arrive at the usual form of this expression:

or

A simple formula for approximating electric power production at a hydroelectric plant is:

P = hrgk

where P is Power in kilowatts, h is height in meters, r is flow rate in cubic meters per second, g is acceleration due to gravity of 9.8 m/s2, and k is a coefficient of efficiency ranging from 0 to 1. Efficiency is often higher with larger and more modern turbines. [8]

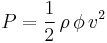

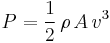

Some hydropower systems such as water wheels can draw power from the flow of a body of water without necessarily changing its height. In this case, the available power is the kinetic energy of the flowing water.

where v is the speed of the water, or with

where A is the area through which the water passes, also

Over-shot water wheels can efficiently capture both types of energy.

Issues

Hydro-powered electricity is not without its drawbacks: Dam failures can be very hazardous, e.g. the Banqiao Dam, which killed 171,000. Also the reservoirs created by the dams can fill with silt and eventually become unable to store enough water to provide water and power in dry weather.[9]

When a dam is constructed it raises the water level and floods large areas of land which is often the most fertile in the area. This can be devastating for the locul population, who must be resettled elsewhere—often on less fertile land.[10]

In addition, hydropower can negatively impact both the flow and quality of water; lower levels of oxygen in the water can present a threat to animal and plant life.[11] Ways of addressing these issues include the installation of fish ladders to ensure safe passage for fish around the area, and regular water aeration to maintain adequate oxygen levels.[11]

See also

- Deep lake water cooling

- Euro Quebec hydro hydrogen project

- International Hydropower Association (IHA)

- Micro hydro

- Renewable energy

- Small hydro

- Trompe

References

- ↑ Kreis, Steven (2001). "The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England". The history guide. http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/lecture17a.html. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ Gwynn, Osian. "Dyfi Furnace". BBC Mid Wales History. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/mid/sites/history/pages/dyfifurnace.shtml. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ↑ Jet d'eau (water foutain) on Geneva Tourism

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hydroelectric power water use USGS

- ↑ Ashden Awards. "The power of water electrifies remote Andean villages". http://www.ashdenawards.org/winners/practicalaction. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ↑ Fieldstoneenergy.com

- ↑ Standard gravity is 9.80665 m/s2

- ↑ Donald G. Fink and H. Wayne Beaty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-07020974-X pp. 9-3 and 9-4

- ↑ Extreme Siltation, a Case Study Retrieved 02sep2009

- ↑ BBC.co.uk

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Energy.gov

- Micro-hydro power, Adam Harvey, 2004, Intermediate Technology Development Group, retrieved 1 January 2005 from ITDG.org

- Microhydropower Systems, US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 2005

- Allan. April 18, 2008. Undershot Water Wheel. Retrieved from Builditsolar.com

- Shannon, R. 1997. Water Wheel Engineering. Retrieved from Permaculturewest.org.au

External links

- International Hydropower Association

- International Centre for Hydropower (ICH) hydropower portal with links to numerous organizations related to hydropower worldwide

- Practical Action (ITDG) a UK charity developing micro-hydro power and giving extensive technical documentation.

- $11 Million Dedicated To Water Power Research.

|

|||||